How Does The Moon Affect Animal Behavior

Science News for Students is celebrating the 50th ceremony of the moon landing, which passed in July, with a iii-function series about Earth'south moon. In part one, Science News reporter Lisa Grossman visited rocks brought back from the moon. Function two explored what astronauts left on the moon. And check out our archives for this story about Neil Armstrong and his pioneering 1969 moonwalk.

Twice a month from March through August, or so, crowds of people gather on Southern California beaches for a regular evening spectacle. As onlookers lookout man, thousands of silvery sardine look-alikes lunge equally far onto shore every bit possible. Before long, these pocket-size writhing, grunion carpet the beach.

The females dig their tails into the sand, so release their eggs. Males wrap around these females to release sperm that will fertilize these eggs.

This mating ritual is timed past the tides. So are the hatchings, some 10 days later. The emergence of larvae from those eggs, every two weeks, coincides with the peak high tide. That tide will wash the baby grunion out to body of water.

Choreographing the grunion's mating trip the light fantastic and mass hatchfest is the moon.

Many people know that the moon'due south gravitational tug on the Earth drives the tides. Those tides too exert their ain power over the life cycles of many coastal creatures. Less well-known, the moon also influences life with its light.

Explainer: Does the moon influence people?

For people living in cities afire with bogus lights, it can be hard to imagine how dramatically moonlight can change the night landscape. Far from any bogus low-cal, the difference betwixt a full moon and a new moon (when the moon appears invisible to u.s.) can be the departure between being able to navigate outdoors without a flashlight and not existence able to run across the hand in forepart of your face.

Throughout the beast world, the presence or absenteeism of moonlight, and the predictable changes in its brightness across the lunar wheel, can shape a range of important activities. Among them are reproduction, foraging and communication. "Light is peradventure — maybe simply subsequently the availability of . . . nutrient — the most important ecology commuter of changes in beliefs and physiology," says Davide Dominoni. He's an ecologist at the University of Glasgow in Scotland.

Researchers have been cataloging moonlight's furnishings on animals for decades. And this work continues to plough up new connections. Several recently discovered examples reveal how moonlight influences the behavior of lion prey, the navigation of dung beetles, the growth of fish — fifty-fifty birdsong.

Beware the new moon

Lions of the Serengeti in the East African nation of Tanzania are night stalkers. They're most successful at ambushing animals (including humans) during the darker phases of the moon'southward cycle. But how those prey respond to changing predator threats as the night's low-cal changes throughout a calendar month has been a nighttime mystery.

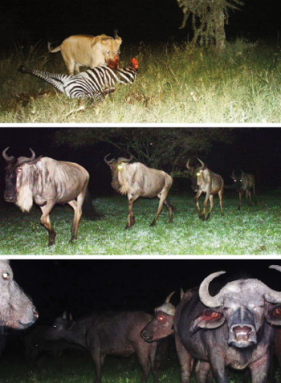

Lions (top) hunt best during the darkest nights of the lunar month. Wildebeests (middle), avoid places where lions roam when it'south dark, photographic camera traps show. African buffalo (bottom), another lion prey, may form herds to stay safe on moonlit nights.

M. Palmer, Snapshot Serengeti/Serengeti Lion Project

Meredith Palmer is an ecologist at Princeton University in New Jersey. She and colleagues spied on iv of the lions' favorite prey species for several years. The scientists installed 225 cameras across an expanse almost as big equally Los Angeles, Calif. When animals came by, they tripped a sensor. The cameras responded by snapping their pictures. Volunteers with a citizen science project chosen Snapshot Serengeti then analyzed thousands of images.

The prey — wildebeests, zebras, gazelles and buffalo — are all plant eaters. To meet their nutrient needs, such species must fodder ofttimes, even at night. The aboveboard snapshots revealed that these species respond to irresolute risks beyond the lunar cycle in different ways.

Common wildebeest, which make up a tertiary of the lion nutrition, were the most attuned to the lunar cycle. These animals appeared to fix their plans for the entire night based on the moon's phase. During the darkest parts of the calendar month, Palmer says, "they'd park themselves in a safety area." Simply equally the nights got brighter, she notes, wildebeests were more willing to venture into places where run-ins with lions were likely.

Weighing as much as 900 kilograms (about 2,000 pounds), the African buffalo are a lion's near daunting prey. They as well were least likely to alter where and when they foraged throughout the lunar bicycle. "They but sort of went where the food was," Palmer says. But as nights got darker, the buffalo were more likely to course herds. Grazing this way might offer safety in numbers.

Plains zebras and Thomson's gazelles also changed their evening routines with the lunar cycle. Just dissimilar the other prey, these animals reacted more directly to changing light levels across an evening. Gazelles were more than active later on the moon had come up. Zebras "were sometimes upwards and about and doing things before the moon had risen," Palmer says. That may seem like risky behavior. She notes, notwithstanding, that being unpredictable might be a zebra's defense: Only proceed those lions guessing.

Palmer'south team reported its findings two years agone in Ecology Letters.

These behaviors in the Serengeti actually demonstrate the broad-reaching effects of moonlight, Dominoni says. "It'southward a beautiful story," he says. It offers "a very clear case of how the presence or absence of the moon can have fundamental, ecosystem-level impacts."

Nighttime navigators

Some dung beetles are active at night. They depend on moonlight as a compass. And how well they navigate depends on the phases of the moon.

In South African grasslands, a dung pat is like an haven for these insects. It offers scarce nutrients and water. No wonder these debris depict a crowd of dung beetles. 1 species that comes out at night to grab and go is Escarabaeus satyrus. These beetles sculpt dung into a ball that's ofttimes bigger than the beetles themselves. Then they whorl the ball away from their hungry neighbors. At this indicate, they will bury their ball — and themself — in the ground.

Some dung beetles (1 shown) utilise moonlight as a compass. In this arena, researchers tested how well the insects could navigate nether different dark sky conditions.

Chris Collingridge

For these insects, the most efficient getaway is a straight line to a suitable burial spot, which tin can be many meters (yards) away, says James Foster. He'southward a vision scientist at Lund University in Sweden. To avoid going in circles or landing back at the feeding frenzy, beetles look to polarized moonlight. Some lunar low-cal scatters off gas molecules in the atmosphere and becomes polarized. The term means that these low-cal waves tend to now vibrate in the aforementioned plane. This process produces a blueprint of polarized lite in the heaven. People tin can't come across it. Simply beetles may use this polarization to orient themselves. It might permit them to effigy out where the moon is, even without seeing it directly.

In recent field tests, Foster and his colleagues evaluated the strength of that betoken over dung-beetle territory. The proportion of light in the nighttime sky that's polarized during a almost full moon is similar to that of polarized sunlight during the day (which many daytime insects, such every bit honeybees, utilise to navigate). As the visible moon begins to shrink in coming days, the night sky darkens. The polarized betoken also weakens. By the time the visible moon resembles a crescent, beetles will take trouble staying on course. Polarized lite during this lunar phase may be at the limit of what the dung harvesters can detect.

Scientists Say: Light pollution

Foster'southward squad described its findings, last Jan, in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

At this threshold, light pollution could get a problem, Foster says. Artificial light tin can interfere with patterns of polarized moonlight. He is conducting experiments in Johannesburg, Due south Africa, to see if city lights affect how well dung beetles navigate.

Like a grow lamp

In the open ocean, moonlight helps infant fish grow.

Many reef fish spend their infancy at sea. That may exist considering deep waters make a safer nursery than does a predator-packed reef. Merely that's just a estimate. These larvae are as well tiny to rail, notes Jeff Shima, then scientists don't know a lot nearly them. Shima is a marine ecologist at Victoria Academy of Wellington in New Zealand. He's recently figured out a way to detect the moon'due south influence on these baby fish.

The common triplefin is a pocket-size fish on New Zealand's shallow rocky reefs. After nigh 52 days at sea, its larvae are finally large plenty to become back to the reef. Fortunately for Shima, adults carry an archive of their youth within their inner ears.

Moonlight boosts the growth of some immature fish, similar the common triplefin (an adult shown, bottom). Scientists discovered this by studying the fish's otoliths — inner ear structures that have tree-ring-like growth. A cross section, nigh a hundredth of an inch broad, is shown under a lite microscope (top).

Daniel McNaughtan; Becky Focht

Fish accept what are known as ear stones, or otoliths (OH-toh-liths). They are made from calcium carbonate. Individuals abound a new layer if this mineral every day. In much the same way as tree rings, these ear stones record patterns of growth. Each layer'south width is a key to how much the fish grew on that twenty-four hour period.

Shima worked with marine biologist Stephen Swearer of the University of Melbourne in Australia to lucifer up otoliths from more 300 triplefins with a agenda and weather data. This showed that larvae abound faster during bright, moonlit nights than on dark nights. Even when the moon is out, yet covered by clouds, larvae won't grow as much as on clear moonlit nights.

And this lunar event is not trivial. It'south about equal to the effect of h2o temperature, which is known to greatly affect larval growth. The advantage of a full moon relative to a new (or dark) moon is like to that of a one-degree Celsius (ane.8-degrees Fahrenheit) increment in h2o temperature. The researchers shared that finding in the January Ecology.

These baby fish hunt plankton, tiny organisms that drift or bladder in the water. Shima suspects that bright nights enable larvae to better see and chow down on those plankton. Similar a child's reassuring night-light, the moon's glow may allow larvae to "relax a bit," he says. Likely predators, such as lantern fish, shy away from moonlight to avert the bigger fish that hunt them by calorie-free. With nothing chasing them, larvae may exist able to focus on dining.

Simply when immature fish are set up to get reef dwellers, moonlight might at present pose a risk. In one study of young sixbar wrasses, more than half of these fish coming to coral reefs in French Polynesia arrived during the darkness of a new moon. But xv percent came during a total moon. Shima and his colleagues described their findings final year in Ecology.

Because many predators in coral reefs hunt by sight, darkness may give these young fish the best chance of settling into a reef undetected. In fact, Shima has shown that some of these wrasses appear to stay at sea several days longer than normal to avoid a homecoming during the full moon.

Bad moon rising

Moonlight may flip the switch in the daily migration of some of the ocean's tiniest creatures.

Scientists Say: Zooplankton

Some plankton — known as zooplankton — are animals or animal-like organisms. In the seasons when the dominicus rises and sets in the Chill, zooplankton plunge into the depths each morning time to avoid predators that chase past sight. Many scientists had assumed that, in the middle of the sunless winter, zooplankton would take a break from such daily up-and-down migrations.

"People generally had thought that there was null really going on at that time of yr," says Kim Last. He's a marine behavioral ecologist at the Scottish Clan for Marine Science in Oban. Simply the light of the moon appears to take over and direct those migrations. That's what Last and his colleagues suggested three years agone in Current Biology.

Scientists Say: Krill

These winter migrations take identify all across the Arctic. Oban's group institute them by analyzing data from sound sensors stationed off Canada, Greenland and Kingdom of norway, and near the Due north Pole. The instruments recorded echoes as sound waves bounced off swarms of zooplankton as these critters moved up and down in the sea.

The moon is the main source of calorie-free for life in the Arctic during winter. Zooplankton such as these copepods time their daily up and downward trips in the ocean to the lunar schedule.

Geir Johnsen/NTNU and UNIS

Normally, those migrations by krill, copepods and other zooplankton follow a roughly circadian (Sur-KAY-dee-un) — or 24-hour — cycle. The animals descend many centimeters (inches) to tens of meters (yards) into the ocean around dawn. So they rise back toward the surface at night to graze on plantlike plankton. But winter trips follow a slightly longer schedule of about 24.8 hours. That timing coincides exactly with the length of a lunar day, the fourth dimension it takes for the moon to rise, set and and then begin to rise once more. And for about half-dozen days around a full moon, the zooplankton hide particularly deeply, downwards to 50 meters (some 165 feet) or so.

Scientists Say: Copepod

Zooplankton seem to have an internal biological clock that sets their sunday-based, 24-hour migrations. Whether the swimmers also accept a lunar-based biological clock that sets their winter journeys is unknown, Terminal says. Simply lab tests, he notes, show that krill and copepods have very sensitive visual systems. They can detect very depression levels of light.

Moonlight sonata

The calorie-free of the moon even influences animals that are active past day. That'southward what behavioral ecologist Jenny York learned while studying minor birds in South Africa's Kalahari Desert.

These white-browed sparrow weavers live in family groups. Year-circular, they sing as a chorus to defend their territory. But during the breeding flavour, males also perform dawn solos. These early morning songs are what brought York to the Kalahari. (She now works in England at the University of Cambridge.)

Male white-browed sparrow weavers (left) sing at dawn. Behavioral ecologist Jenny York learned that these solos begin earlier and concluding longer when there'southward a full moon. York (right) is shown here trying to take hold of a sparrow weaver from a roost in Due south Africa.

FROM LEFT: J. YORK; DOMINIC CRAM

York awoke at three or 4 a.chiliad. to arrive at her field site before a performance began. But on one bright, moonlit morn, males were already singing. "I missed my data points for the day," she recalls. "That was a bit annoying."

So she wouldn't miss out over again, York got herself up and out earlier. And that's when she realized the birds' early offset fourth dimension was not a one-day accident. She discovered over a seven-calendar month flow that when a full moon was visible in the sky, males started singing an average of most 10 minutes earlier than when there was a new moon. York'southward team reported its findings five years agone in Biology Letters.

Classroom questions

This extra light, the scientists concluded, kick-starts the singing. After all, on days when the full moon was already below the horizon at dawn, the males started crooning on their normal schedule. Some Due north American songbirds seem to have the same reaction to the moon's light.

The earlier first time lengthens the males' average singing period past 67 percent. Some devote simply a few minutes to dawn singing; others keep for 40 minutes to an hr. Whether in that location'south a benefit to singing earlier or longer is unknown. Something near dawn songs may help females evaluate potential mates. A longer operation may very well assist the females tell "the men from the boys," every bit York puts it.

Source: https://www.sciencenewsforstudents.org/article/moon-has-power-over-animals

Posted by: shooptandinque.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Does The Moon Affect Animal Behavior"

Post a Comment